What do plants on sheets, insects on pins, and frogs in jars have to do with entrepreneurship?

Naturalists and scientists have been collecting butterflies, pressing plants, and catching fish to document the evolution, radiation, and diversity of the world’s organisms since the early 1700s. These preserved voucher specimens have been locked away in research and private collections for centuries, difficult to access even by scientists who didn’t know where everything was. Close to 15 years ago, the National Science Foundation created iDigBio as the U.S. hub for digitizing and mobilizing biological collections data. iDigBio led by elevating members of the community doing digitization well and then they built the foundation to aggregate the data created during this work. Its servers on the University of Florida campus currently host over 147 million specimen records and 66 million associated media files.

In December 2023, I joined the team at iDigBio as an embedded entrepreneur to explore mission-aligned pathways to sustainability for one of the largest and most important scientific data infrastructures in the country.

This work was part of a larger initiative launched by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and NobleReach Emerge to help research infrastructure projects transition toward broader impact and long-term viability. iDigBio was selected as one of just eleven projects nationwide to participate in this visionary program supporting research translation and sustainability.

Read the press release

Our cohort of science infrastructure projects faced a shared challenge: how do you sustain open, mission-critical data platforms without a built-in revenue model?

What Science Entrepreneurship Looked Like in Practice

The goal wasn’t a commercial spinout, but rather a durable structure to support iDigBio’s mission and values.

My work as an embedded entrepreneur centered on strategic discovery, stakeholder alignment, and identifying viable, mission-consistent revenue models for long-term sustainability. This included conducting over 70 interviews with biodiversity scientists, collections professionals, policy experts, and applied ecologists to map community needs and emerging opportunities. We talked to people familiar with iDigBio and those we thought would benefit but did not (yet) use biodiversity specimen data for environmental decision-making.

We found common challenges around incomplete data, technical aspects of mobilizing these data (for data publishers), and locating cleaned, relevant data at scale for research. We heard many calls for the digital extended specimen, especially integration with genetic sequence data. Several interviewees expressed an interest in a natural language chat-like interface for finding what they sought in the database (yes, this is foreshadowing).

We found that people not yet familiar with iDigBio did not understand the scope of its work at first glance, and so we refreshed the homepage and included new calls to action for corporate sponsorship and data services.

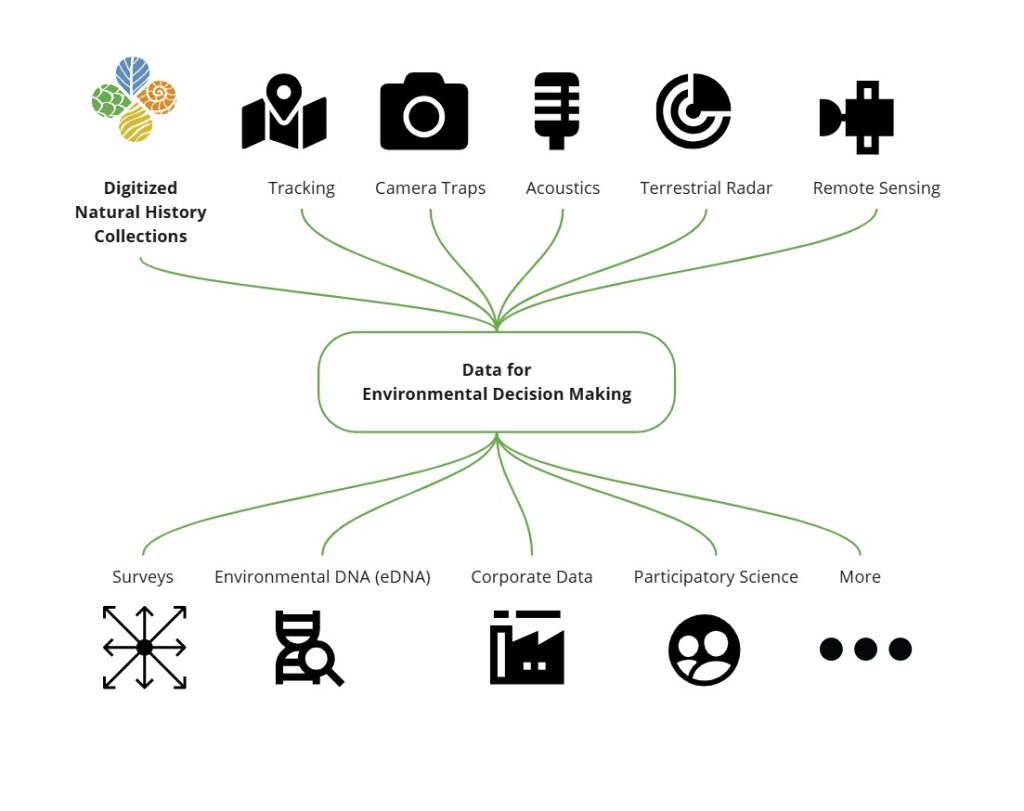

We used the identified community needs to guide internal and community conversations around sponsorship, data services, philanthropic funding, and operational partnerships. We outlined a vision where digitized biodiversity and extended specimen data underpin research, policy, and economic decision-making. These specimen data provide an unmatched historical baseline for environmental monitoring.

A Passionate, Collaborative Community

iDigBio’s strength lies in its community—curators, technologists, researchers, and collections professionals committed to making biodiversity data available, discoverable, and useful. I was fortunate to work alongside existing partners—AIBS, NSCA, and SPNHC—and to initiate conversations with related organizations such as the Nature Tech Collective, a dynamic network of researchers, technologists, and entrepreneurs exploring the intersection of nature and data.

For example, Gil Nelson, iDigBio’s Director, spoke on “The Power of Digitized Voucher Records for Biodiversity Monitoring” at the Nature Tech Collective NTC Now webinar in June 2024, highlighting how specimen data supports real-time environmental decision-making.

Field Notes from a Mostly Remote Year

While most of this work took place remotely, there were energizing in-person moments along the way. We kicked off with an in-person meeting in Gainesville, and then I traveled to Tempe to meet with the Symbiota team. I joined the community at Digital Data 8 in Lawrence, Kansas, and participated in the Advances in Digital Media workshop at Yale in New Haven, Connecticut. While most of the interviews were online, I jumped at the chance to visit and collaborate in person with researchers at the University of Michigan Research Museum Center here in Ann Arbor.

Although remote, it was hardly a lonesome year. The online collaboration was lively, with good humor and critical thinking in equal measure. We were buoyed by the enthusiasm and creativity shown by every community member we interviewed or met in person. iDigBio really had a strong community, valued what they had received, and were eager to participate in shaping our sustainability planning.

No Missed Jackpot — But Plenty of Insight

At Digital Data 8, iDigBio held a session on sustaining scientific infrastructure, including experts from iDigBio, Environmental Data Initiative, MorphoSource, NobleReach, Specify Collections Consortium, and USA National Phenology Network. Leads of these important community resources spoke to the attendees about lessons learned and challenges faced as they transitioned from NSF grant funding to something more community-supported. More recently, the USA National Phenology Network, published a paper with their embedded entrepreneur showing their work on this topic: their future sustainability likely lies in a blend of public funding, grants, philanthropy, and mission-aligned service offerings.

Read their perspective

Our team, like others in the NSF/NobleReach cohort, faced a hard truth: open scientific infrastructure doesn’t often produce the kind of intellectual property that drives university spinouts. That openness is a feature, not a flaw, but it does complicate the business model.

This experience deepened my conviction that science entrepreneurship doesn’t always mean spinning out a product or chasing a venture-scale outcome. Sometimes, it means protecting and evolving open infrastructure in ways that preserve its value and grow its impact. Increasing access to these data is a key principle, and so many congratulations to the advanced computing and information systems team at University of Florida for launching the biodiversity chatbot: iChatBio this spring.

Deep Gratitude for Thoughtful Collaboration

Working with the iDigBio team was one of the most rewarding parts of this project. Their open, good-natured, and thoughtful collaboration made it a joy to contribute to such an important and community-centered initiative. I’m especially grateful for the opportunity to work alongside:

- Gil Nelson, whose enthusiasm, warmth, and commitment to inclusion sustained the team and shaped the spirit of this engagement from day one—I learned so much from his deep belief in iDigBio’s people and mission.

- Austin Mast, who brought long-term strategic vision and a sustainability mindset to both iDigBio and the Digitization Academy, and whose thoughtful questions pushed the work forward.

- Jose Fortes, who brought focus to scale and systems, and always contributed unexpected, generous observations that deepened the conversation.

- Pam Soltis, who regularly recentered the group on iDigBio’s integrated vision, shared valuable global insights drawn from her broad scientific engagements, and—along with her students—kept us focused on the ecological and environmental applications of these data.

- Libby Ellwood, a generous collaborator whose broad community perspective helped align vision with action—from partnership development to keeping iDigBio focused on its core strengths.

- Nico Franz, whose work on Symbiota exemplified practical sustainability and who brought intellectual energy and a willingness to challenge assumptions that helped refine our thinking.

- David Jennings, whose critical thinking, organizational rigor, and steady support helped hold the team together—his candor and guidance were key to every piece of progress we made.

- The teams at the University of Florida, Florida Museum, Florida State University, and University of Kansas that I had the pleasure of meeting and who gave generously of their time, wisdom, and wit throughout the project.

I’m proud of the work we did and inspired by the community I met. As iDigBio and others continue integrating biodiversity data into the decisions shaping our planet, I’ll be cheering from the sidelines—and seeking out the next opportunity to connect science, data, and sustainability at scale.